The group of Honors College students and faculty explored the newest Smithsonian museum and sat down with Professor Crew for a discussion.

“The first object which saluted my eyes when I arrived on the coast, was … a slave ship … waiting for its cargo,” said Olaudah Equiano, an African writer and abolitionist, in 1789.

This is one of the first quotes that visitors are met with when entering the “Slavery and Freedom” exhibit at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC). The exhibit metaphorically sends visitors back in time through the beginnings of the African-European relationship and ends in the Reconstruction era.

As visitors time travel through the early stages of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, they encounter artifacts like Harriet Tubman’s shawl, Frederick Douglass’s cane, and the original documents for the Emancipation Proclamation and the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments.

They also see shackles, whips, pieces of slave ships, and sorrowful quotes from those suffering under the oppressive rule of slavery. These chilling artifacts create a heavy atmosphere as visitors move through the exhibit.

Robinson Professor Spencer Crew discusses the museum with students and faculty. Photo by Lathan Goumas, Creative Services.

On Friday, March 22, a group of Honors College students and faculty witnessed this history for themselves.

The group was introduced to the museum by George Mason Robinson Professor Spencer Crew, who serves as a curator at the museum for the exhibit focused on segregation. Professor Crew informed the group of the history of the NMAAHC itself and what to expect when navigating the museum.

The concept of a museum that highlighted and celebrated the Black experience in America has been in discussion for over 100 years. Professor Crew explained that a group of African American veterans began petitioning for the museum’s existence to then-President Harding, but their efforts were ignored for nearly a century. It was not until 2003 when Congress passed an act to establish the NMAAHC. Once the museum gained federal support, the questions of what to include and how to present it arose.

It took nearly 13 years to curate, design, and build the museum. The final product represents the culmination of a nationwide preservation program that encouraged and taught people to protect their family histories and the creative minds of artists representing the African diaspora worldwide.

The Honors College group quickly learned that the NMAAHC is unlike other Smithsonian museums in many ways.

One difference is apparent as soon as people see the NMAAHC in comparison to the other museums around it. Professor Crew explained how the copper lattice of the exterior was a purposeful design choice to make the museum stand out from the others. The unique shape of the building draws from the art of the Yoruba people in Africa, connecting African Americans to a worldwide Black experience.

The NMAAHC also physically covers expansive ground. The building has ten floors in total: five above ground and five below. The historical exhibits that deal with slavery, freedom, segregation, and post-Civil Rights are all housed underground. The galleries that highlight African Americans in sports, the military, music, film, and visual art are all above ground.

Professor Crew encouraged the Honors College group to explore as much as they could.

A portion of the group started at the very bottom of the museum with the “Slavery and Freedom” exhibit and worked their way through segregation, the exhibit curated by Professor Crew called “Defending Freedom, Defining Freedom: The Era of Segregation 1876-1968.”

Here, the group explored histories like the first all-Black towns, activist Ida B. Wells’s anti-lynching campaign, and the rise of protest organizations. They were also met with disturbing and breathtaking artifacts from dark moments in American history.

In the middle of the exhibit sits a real segregated railcar from the Southern Railway Company in 1923. Visitors of the museum not only have the opportunity to read about the history of segregated cars, but the railcar is open for all to walk through.

Inside, visitors walk down the aisle of the railcar through the “Whites only” section—with its two large restrooms and oversized luggage bin—and into the “Colored” section—which has two much smaller restrooms and lacks an oversized luggage bin. This walk is accompanied by audio clips of children of both races asking their parents why these differences exists. Maintaining the time travelling involved with this part of the museum, visitors are transported to the time of segregation when walking on this railcar and get an authentic glimpse of what life was like during this era.

One of the toughest and most heartbreaking moments of the museum is also housed in this exhibit, sectioned off into its own room with no photography allowed: the Emmett Till memorial.

Till was a 14-year-old African American boy from Chicago visiting Mississippi in 1955 when he was brutally beaten and murdered by two White men for allegedly whistling at a White woman. His story gained an abundance of attention when his mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, decided to have an open-casket funeral despite Till’s face being mutilated beyond recognition. His murder and his mother’s decision are said to have caused a major spark for the Civil Rights Movement.

The NMAAHC has the original casket that he was buried in on display as a donation from Till’s family. The family also requested the no-photography rule out of respect for him.

The room highlighting Till’s story proved to be one of the most difficult moments to move through in the museum. Visitors circled his mini-exhibit slowly, taking in how tragically his life was cut short over something as mundane as an alleged whistle. Similar to the effects of the slavery artifacts, this room left visitors with a heavy cloud of sorrow and a lasting impression for the ruthlessness of racism.

The Honors College group continued on through the last phase of the historical exhibits titled “A Changing America: 1968 and Beyond.” Here, the museum took an uplifting turn, highlighting women like Shirley Chisholm in political movements and the rise of the Black experience represented in popular culture.

Honors College students enjoyed seeing familiar faces like Oprah Winfrey, who currently has her own full exhibit, and artifacts from figures they have grown up with, like a dress worn by former First Lady Michelle Obama.

This final exhibit travelled through the decades to pinpoint monumental times in African American history and culture. Some moments included Anita Hill’s testimony against Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas representing the 1980s and the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina on Black communities representing the 2000s. The election of former President Barack Obama was also heavily featured in the 2000s to 2015 section. Though the decade is not over yet, the NMAAHC has already begun to fill in some important moments from the 2010s.

Once the Honors College group finished exploring the historical exhibits below underground, they moved upstairs to the galleries focused on African American culture.

The community galleries on the third floor represent the Black experience through sports, community activism, location, and the military. Professor Crew had earlier told the Honors College group that the military exhibit overlooked the Arlington National Cemetery.

In the sports section, figures like Michael Jordan and Serena and Venus Williams are honored through life-size statues of them. The players and teams mentioned all have contributed to the world of sports and social/political movements, reinventing the notion of what an athlete can do beyond their arena. Other people and teams the Honors College group learned about included Muhammad Ali, the Harlem Globetrotters, and Paul Robeson, whom the African and African American Studies Research and Resource Center at George Mason University is named after.

The gallery also included protest signs from marches, writer James Baldwin’s passport, and desks from an early 1900s African American school. A highlight from the gallery that caused the group to reflect upon was a real cell from the Louisiana State Penitentiary, which was built on an infamous slave plantation known as Angola. This fact connects slavery with the prison system in a tangible and horrifying way.

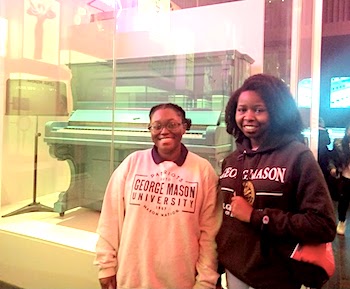

Honors College students Zaria Talley (the author) and Doreen Joseph

One floor up from the community galleries are the culture galleries. Here, students continued to enjoy seeing parts of their upbringings and childhoods forever memorialized.

The first thing many noticed about the space was its unique design. The culture gallery opens up with an introductory area that is shaped like a circle. Screens line the walls of the entire room as clips of artists, actors, and creatives play for all to enjoy. The gallery then breaks off into different rooms showcasing these cultural icons through personal artifacts and stunning photography.

The music room, called “Musical Crossroads,” welcomed visitors with Chuck Berry’s cherry red Cadillac sitting at the door. From there, the Honors College group explored the various genres on display, like jazz and rock & roll, and the musical accomplishments of Black artists, like one of Whitney Houston’s 1987 American Music Awards.

There are multiple walls listing artists who have impacted the music landscape, and the Honors College students searched to find their favorite artists’ names. Stage outfits worn by artists like Earth, Wind, & Fire, Prince, and Diana Ross sit in glass cases for visitors to awe at, and snippets of iconic songs by Black artists play over the speakers. The room sparked joy in those who strolled through it and was a favorite among the Honors College group.

The group’s time in the NMAAHC came to end in what felt like seconds. Soon, they sat back down with Professor Crew to discuss their favorite moments in the museum and directions they would like to see the museum take. Both students and faculty found spaces like the “Slavery and Freedom” exhibit deeply troubling but valued seeing moments from history come to life before their eyes. Each person left with new pieces of knowledge that they were not aware of before.

Professor Crew told the group that visitors often find they have to plan a second, third, or even fourth trip to the museum to see everything that they may have missed. With a collection of over 30,000 artifacts, it is easy to overlook something or run out of time. The Honors College group left the museum with a better understanding of African American history and culture and plans for their next visit to the NMAAHC.

Reporting by Zaria Talley